- Mark Longhurst

James Baldwin and 1 John on Love and White Racism

You can feel an epoch crumbling, a society on the verge of either finding its soul, collapse, or both. The rage and passion for justice we are witnessing on American, no, global streets in the wake of George Floyd’s murder reveals a spiritual awakening. Or, better yet, we are invited to an unveiling of reality, which is the meaning, in Greek, of apocalypse (apokalypsis). The reality we are invited to see is the reality of systemic, racist violence against Black-skinned bodies. The violence has been there from the beginning of the American project, of course—but those of us with white-skinned bodies could deny the trauma we inflicted on Black and Brown bodies, and postpone the healing work it would take to be free from our complicity in violence. We conveniently clutched the unearned privilege that the system gifted us—and took more. And now, the time of unveiling is here. As the old labor union song goes, “Which side are you on?”

I don't have much energy these days, what with full time work and parenting happening simultaneously. It's all I can do to stay grounded, remain faithful to a small group of friendships, present and playful with my kids, and double down on my contemplative practices (now, more than ever!) But rereading the work of James Baldwin is always a worthwhile enterprise. Never more so than now, of course, when we are living what he prophesied over fifty years ago: "No more water; the fire next time." As Jesmyn Ward perceives, we have been and are living in the "Fire this time."

So, here's an old sermon, based on 1 John and James Baldwin's address to the World Council of Churches entitled "White Racism or World Community." For Christians, it's an important time, I believe, for us to reckon not only with the white supremacy of American society, but also the white Christian supremacy, and how the two have been linked since the beginning of the US colonies. There is the religion of the slaveholder, and the religion of Christ, Frederick Douglass said. Christians are being forced to decide which Christianity, which Jesus, they belong to.

James Baldwin, in 1968, is angry. Martin Luther King Jr. has been shot. Three years before, Malcolm X is shot. The 1963 murder of NAACP Mississippi Field Secretary Medgar Evers still hangs heavy over Baldwin’s consciousness. It is becoming clear that nonviolent protest against segregation is not enough to change the structures of white supremacy in the United States. The head of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, Stokely Carmichael, has made the concept of black power go viral. And after King’s killing, something inside the country’s psyche, and in Baldwin’s heart, breaks. His essay 1963 The Fire Next Time is becoming prophecy as cities across the country are burning, cities like Washington D.C., Baltimore, and Chicago.

Before his death, Martin Luther King had been scheduled to give an address at the esteemed World Council of Christian Churches in Geneva, Switzerland. James Baldwin is asked to fill in. James Baldwin is the son of a preacher, he is a one-time preacher himself. He is, for years, a scathing critic of institutional Christianity. He is a black and gay man who did not feel welcomed in his church. He is a devastatingly beautiful writer, and he stands in front of the clergy and lay leaders of the World Council of Christian Churches, and James Baldwin preaches a sermon. It’s called “White Racism or World Community.”

But it’s not the sermon that King would have given. And it’s not a sermon that you would hear in any church. It’s a sermon by, Baldwin says, “one of the creatures, one of God’s creatures, whom the Christian Church has most betrayed.” It’s a loving sermon, but a hard sermon, a sermon that names the hypocrisy of white Christianity to live up to the ideals of Jesus. It contains an accusation of hypocrisy, but also a plea, Baldwin says, a plea straight from the lips of Jesus, “Insofar as you have done it until the least of these, you have done it to me.”

“God is love,” 1 John reads, “and those who abide in love abide in God, and God abides in them.” And yet Baldwin’s agony is that precisely those who say they abide in God are not the ones who have actually abided in love. “Part of the dilemma,” he says, “of the Christian Church is the fact that it opted for power and betrayed its own first principles which were a responsibility to every living soul…that all men are sons of God and all men are free in the eyes of God and are victims of the commandment given to the Christian Church, “Love one another as I have loved you.”

Do you see? None of us identifying as white Christians in the United States are able to remain untainted by the past. We are all condemned—not by God, but certainly by Baldwin, as well as by our conscience and history, because the very structures of Christianity in our country are complicit in the buying, selling and brutality against black bodies and brown bodies. This is the terror of love because if we are to love in Baldwin’s sense, we have to face our histories. Not only our personal histories, but the collective histories in which we are all bound up. If there is a contemporary retrieval possible for the word “sin,” this is what it might mean.

There’s even a more subtle systemic critique than that of white supremacy here that Baldwin is making: Christianity’s alignment with state power, or state power’s seduction of Christianity, first in the fourth century, and continuing to this day (even in spite of constitutional separation of church and state) is a betrayal of the witness and message of Jesus. As one scholar writing about Baldwin puts it, “Baldwin could never make his peace with a religious tradition that began with the teachings and sacrifices of an outcast teacher and ended with the authoritarian values of white property owners.” (David Hempton, Evangelical Disenchantment). In the hands of power, the nonviolent, loving revolutionary Jesus becomes something else entirely.

“Love has been perfected among us in this: that we may have boldness on the day of judgment, because as he is, so are we in this world.” The Greek word for “boldness or “confidence” can also mean frankness or openness. Christians who dare to use the name, who believe and live like Jesus, are the ones who are free, who are “frank” in our assessment of reality and each other, and who maintain an openness to God, a readiness to love. For those separated from love, separated from God, there is indeed fear, fear of facing reality, fear of change, fear of accountability for our collective actions—maybe this is the contemporary meaning of the day of judgment?—but for those who love, there is a bold confidence about the future.

Love transforms our present and future—it “perfects” us, or better yet, to bring another angle from the Greek, love makes us whole. Those who love are those who are already experiencing an unhindered flow of relationship between God, people, and the world in the present moment. You know people who love by the presence of their love. The future may, indeed, be bleak—but not even a day of judgment, or dire headlines, ominous studies, or crises and upheaval can unmoor the true lover.

“There is no fear in love, but perfect love casts out fear, for fear has to do with punishment, and whoever fears has not reached perfection in love.” There is no fear in love, for fear has to do with punishment. And yet, for Baldwin, white Christianity itself is built on the fear of, and the brutal reality of, punishment and violence. Of instilling fear, instead of love. “We won our Christianity, our faith,” Baldwin says, “at the point of a gun, not because of the example afforded by white Christians, but in spite of it. It was very difficult to become a Christian if you were a black man on a slave ship and the slave ship was called “The Good Ship Jesus.”

To love means to be fearless, and to divest oneself of the need for punishment. Baldwin’s pursuit of love compelled him, ironically, out of the church, because he did not find the love of Christ there. He says, “the Christ I was presented with was presented to me with blue eyes and blond hair, and all the virtues to which I, as a black man, was expected to aspire had, by definition, to be white.” To find and love himself, and even to find and love Christ, he had to leave behind that blue eyed, blond haired Jesus. He had to leave behind Christianity, paradoxically, to draw closer to the real Christ.

Baldwin has blistering things to say about Christianity, and many people have assumed that he is an atheist. But regardless of his departure from institutional Christianity, he never loses his vocation as a preacher. He preaches to different crowds, of course than Sunday church-going believers, but his essays pulse with the poetic rhythm of Pentecostal preaching and the fierce truth of Hebrew prophecy. The loving witness of Jesus never loses its grip on his consciousness. It haunts him.

Baldwin even “confesses” to be something of a Christian, on several occasions. In a 1971 seven hour-long conversation with anthropologist Margaret Mead, Baldwin says, “what Christians seem not to do is identify themselves with the man they call their Savior who, after all, was a very disreputable person…So, in my case in order to become a moral human being, whatever that may be, I have to hang out with publicans and sinners, whores and junkies, and stay out of the temple where they told us nothing but lies. It is only in that sense,” Baldwin says, “that I can be called a Christian.” (Mead and Baldwin, A Rap on Race)

“Those who say, “I love God,” and hate their brothers or sisters, are liars, for those who do not love a brother or sister whom they have seen, cannot love God whom they have not seen.” For the writer of 1 John, the truth of one’s commitment to love is fairly straightforward: it is not about how much love I experience love between God and myself, it is how I treat people. Baldwin, like the author of 1 John, dares to chastise his Christian contemporaries as being complicit in a lie—the lie that white Christians as a collective system—are loving in spite of the violence against black and brown people in the United States. “If one believes in the Prince of Peace,” he says, “one must stop committing crimes in the name of the Prince of Peace.”

Baldwin preached it to the World Council of Christian Churches then, in 1968, and his words are no less relevant now. The marker of a Christian is not who goes by that name, but who loves. As the old song goes, “You will know they are Christians by their love.”

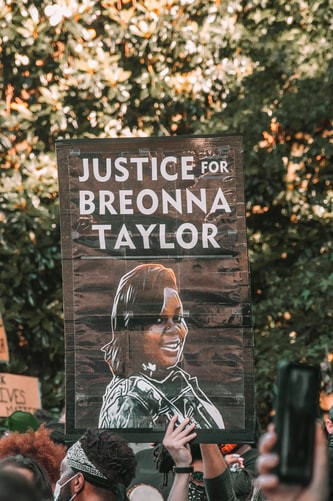

Photo credit: Maria OswaltonUnsplash